Current State

We have a class named StatusService which contains a save() method for persisting StatusModel data to a repository.

Two modules utilize this persistence logic:

- The

StatusServiceitself, which is invoked by aStatusResource(a REST endpoint). - A

ResetStatusclass, which is triggered by aResetStatusEventListener.

The ResetStatus class directly calls a method in StatusService to persist the status data. The name StatusService suggests it acts as a facade or manager for all status-related operations (querying, saving, deleting, etc.), but this design creates hidden pitfalls for testing.

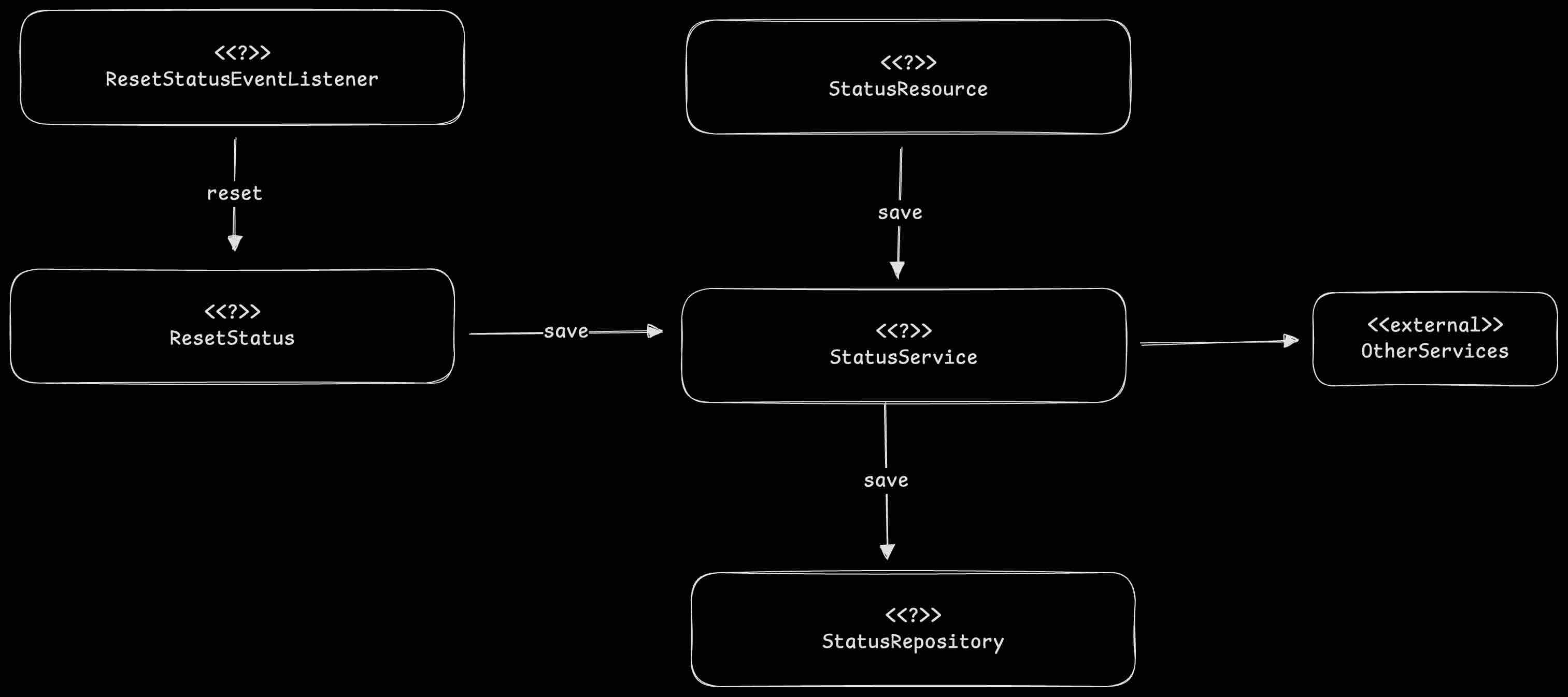

The current logical relationship is illustrated below:

Here are the relevant code snippets:

Here are the relevant code snippets:

// StatusService.java

public void save(final StatusModel statusModel) {

final EntityID id = statusModel.id();

// Business validation logic

guardEntityExists(id);

final List<ExternalInfo> externalInfos = lookupExternalInfo(id, getContext());

guardInfoIsValid(statusModel, externalInfos);

guardSomeBusinessRule(statusModel, externalInfos);

// Data mapping logic

final StatusModel mappedStatusModel = mapDataToMatchExternalInfo(statusModel, externalInfos);

// Persistence and side-effects

final boolean stateHasChanged = statusRepository.save(mappedStatusModel);

if (stateHasChanged) {

log.debug("Invalidating cache for ID={}", id);

cacheService.invalidateCacheForIds(List.of(id.toString()));

}

}It is used by two different modules. The first is:

// StatusResource.java

@PUT

@Path("entities/{id}/status")

public Response updateStatus(

@PathParam("id") final EntityID id,

@Valid final StatusUpdateRequest request) {

statusService.save(mapToDomainModel(id, request.details()));

return Response.ok().build();

}And the second module is:

// ResetStatus.java

public void reset(@NonNull final EntityID id) {

log.info("Invoking factory reset of status for ID={}", id);

final StatusModel currentStatus = statusRepository.findById(id);

final StatusModel resetStatus = currentStatus.withStatusReset();

statusService.save(resetStatus);

}

// ResetStatusEventListener.java

public void handleEvent(final SystemResetEvent event) {

resetStatus.reset(event.getId());

}The Problem Caused by This Structure

During testing, an integration test that calls the reset functionality failed. The error indicated that the entity ID could not be found.

Upon investigation, I discovered that StatusService.update() (originally named save()) contains a guardEntityExists() check. The test case did not set up a corresponding entity, causing the guard to fail. The StatusService was originally designed to serve the StatusResource, and its internal logic was tailored for that specific flow. In other words, the implementation of StatusService.update() was not suitable for the Reset scenario.

This error clearly reveals two distinct Use Cases:

- One for handling requests from the

Resource(an Inbound Adapter). - Another for handling the

Resetrequest from theListener(another Inbound Adapter).

The commonality is that both need to eventually call the repository’s save() method. The key difference is that the Reset use case does not require the guardEntityExists() check.

Analysis

In architectural styles like Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters), we organize our code into layers like Inbound/Outbound Adapters, Use Cases, and the Domain. It’s crucial to correctly classify our existing classes and define how they should interact.

We can clearly classify the following components:

- Inbound Adapter:

ResetStatusEventListener - Inbound Adapter:

StatusResource - Outbound Adapter:

StatusRepository(specifically, its implementation)

This leaves us to classify ResetStatus and StatusService.

The name ResetStatus strongly implies it is a Use Case. Looking at StatusService, we see it contains a mix of logic. It has “anemic” pass-through methods that simply delegate to the repository, such as:

// StatusService

public StatusModel findById(final EntityID id) {

return statusRepository.findById(id);

}At the same time, it includes what should be Domain logic, like lookupExternalInfo() or the aforementioned guardEntityExists(). To simplify for a moment, let’s ignore the domain-like methods and treat the core orchestration logic as another Use Case. We now have two:

- Use Case:

StatusService - Use Case:

ResetStatus

Use Cases should be isolated from one another, but the current structure violates this principle, which is why it “feels” wrong. With this new classification, the path forward becomes clearer.

Refactoring the Structure

In the new structure, ResetStatus should interact directly with its required Outbound Port (StatusRepository) to save the reset status. It should not be coupled to another use case like StatusService.

Additionally, the save() method in StatusService needs to be renamed. The reason is that this method is not “pure”. Besides saving data, it also performs guards, mapping, and cache invalidation. It’s clearly not just “saving” something but orchestrating a process. I would rename it to update() or something similar to reflect its role in orchestrating a complete workflow.

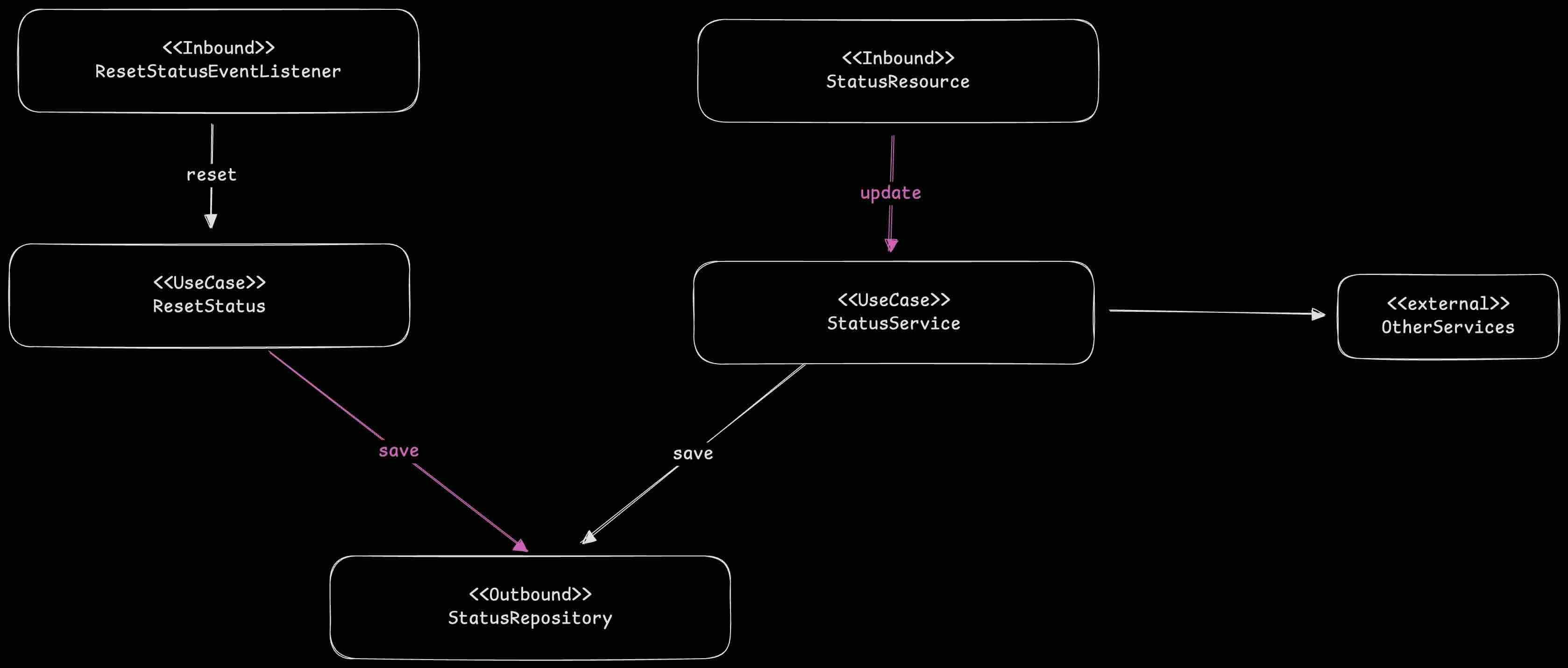

Our new structure now looks like this:

Although the overall structure is clearer, the name StatusService is still confusing. I researched definitions and best practices for Use Cases, and a strong convention emerged: A Use Case class should have only one public method.

The reasons are as follows:

- Single Responsibility Principle (SRP): A class should have only one reason to change. If a class represents a single use case, it will only change when that specific business process changes. If a class contains multiple use cases, a change in one can inadvertently affect others, increasing the risk of bugs.

- Clear Business Boundaries: When you open the application package, you see a list of clearly named Use Case classes (

ActivateFeatureUseCase,UpdateStatusUseCase, etc.). This acts as a menu of the system’s capabilities, making it immediately understandable. - Minimized Dependencies: Different use cases have different dependencies. If they are combined into one class, that class will accumulate all dependencies, even if a specific method doesn’t need them. This leads to dependency clutter and unnecessary coupling.

- Clear Transactional & Security Boundaries: In frameworks like Spring, annotations like

@Transactionalare typically applied to public methods. When a class has only one public method, the transactional and security scope is unambiguous: the entire use case succeeds or fails as a single unit. This avoids the complexity of managing state across multiple methods within a single class.

Following this principle, StatusService should be renamed to UpdateStatusUseCase, and its public method could be named execute() or apply().

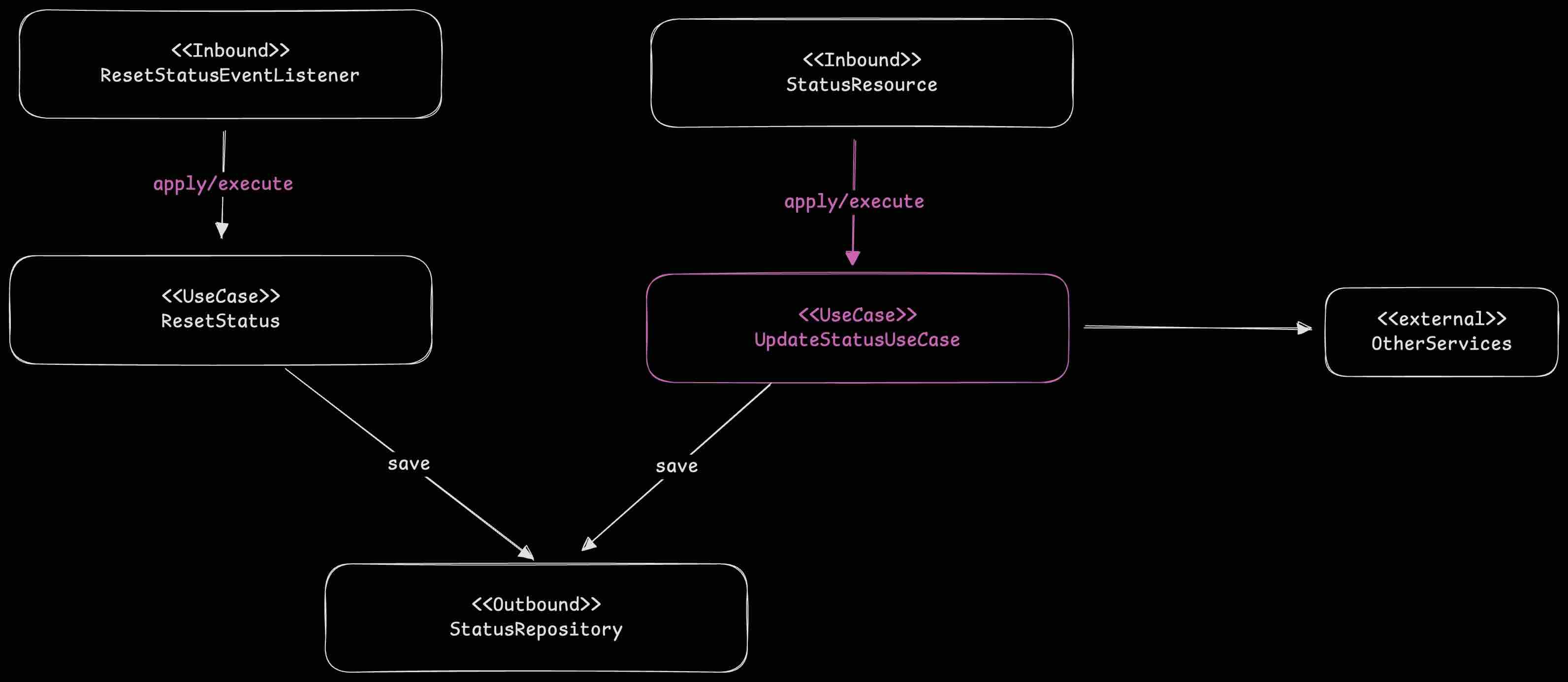

The renamed structure is:

We’ve focused on Use Cases, but let’s briefly touch on the Domain. The Domain layer should contain the actual business rules and logic, not orchestrate workflows or call external services. In our example, methods from UpdateStatusUseCase (the former StatusService) like guardEntityExists(), lookupExternalInfo(), and the StatusModel itself belong in the Domain. Use Cases rely on the Domain for its business logic. For instance, ResetStatus needs knowledge of the StatusModel to correctly reset the status.

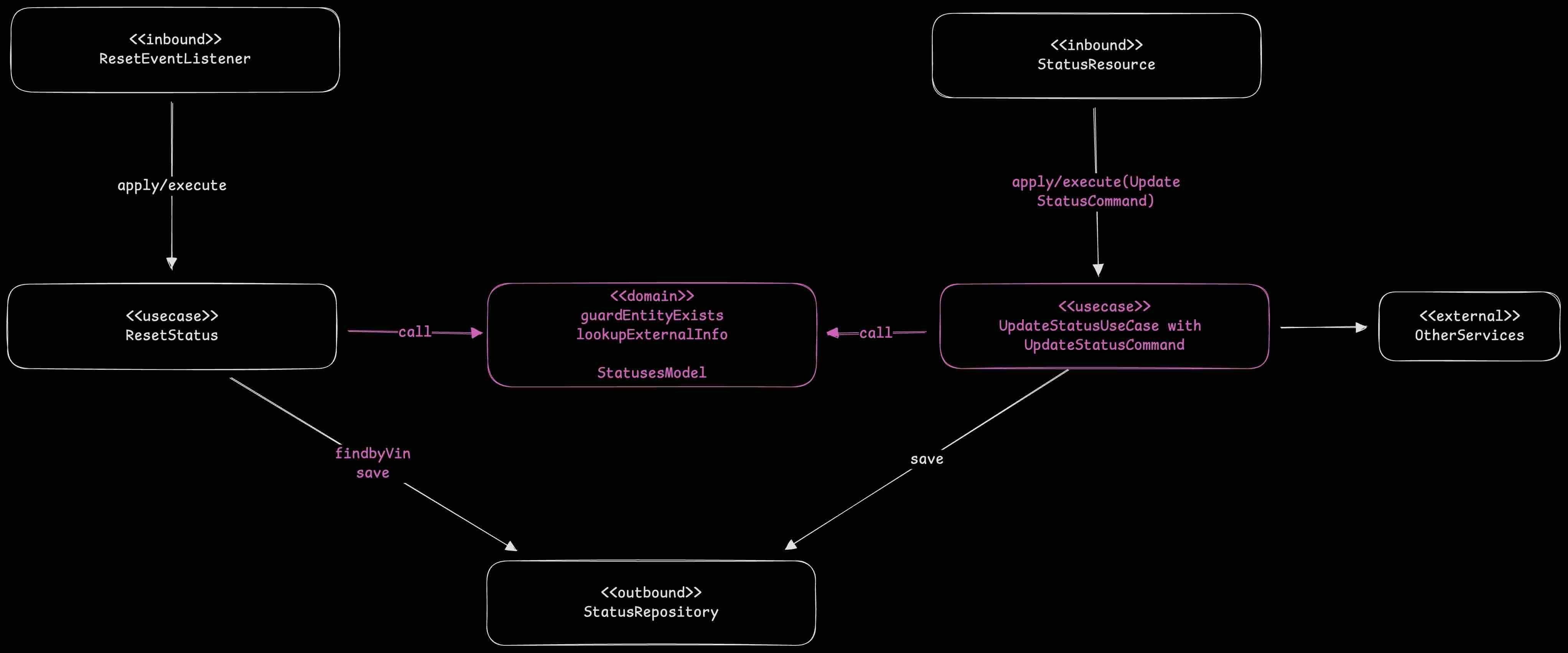

After this final organization, the ideal structure is:

Further Thoughts

I’ve made two observations during this process.

First, discussions about architecture often feel like time-consuming black holes. Second, discussing architecture is a bit like discussing politics or philosophy; everyone, regardless of experience, seems to have an opinion. While the views of experienced architects are naturally more profound and important than those of someone less experienced (like myself), they can easily get lost in a sea of opinions.

It is a high-entropy topic.

Of course, no matter how the architecture changes, its ultimate purpose is to solve real problems. In this case, the problem was getting a specific integration test to pass. By starting with a concrete issue, we were able to reflect on the problematic code, refactor it, and ultimately solve the problem.

If I had been asked to design a “perfectly structured” solution from scratch, I would have felt lost. There is no absolute standard for what is “better” in a vacuum. At a given moment, placing a module A in position 1 versus position 2 might make no functional difference and cause no immediate issues; the choice is often a matter of taste or feel. It’s hard to call these “real problems.” The real problems often only surface after the system is in use, which is also why it’s easy to fall into the trap of over-engineering during the initial design phase.

The true power of architectural design, and the foresight of an experienced designer, can often only be validated over time.

In summary, this simple example allowed me to tangibly understand the high-level definitions of different architectural components and how the design of their boundaries directly impacts the functioning of a real system.